RACHEL AVIV’S STRANGERS TO OURSELVES: UNSETTLED MINDS AND THE STORIES THAT MAKE US is a book about psychiatry, but it is also a book about the self, “the facets of identity that our theories of the mind fail to capture,” one written with an astonishing amount of attention and care. Since Westerners tend to conflate the self with the mind—or at least locate the former inside the latter—behavioral science is a field that implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) presumes to explain why we are the way we are, which is also to say why we are who we are: our chemistry is imbalanced, we’re holding a grudge against our parents, we’ve inherited mental illness, or we’re suppressing sexual urges. These analyses may be accurate or partially accurate, and of course there’s also the disturbing possibility that they’re entirely wrong. But Strangers to Ourselves looks beyond that inquiry to examine the project of determining “who” someone is. Explanations, labels, and diagnoses—whether or not they’re correct—circumscribe the self and can therefore create problems of their own.

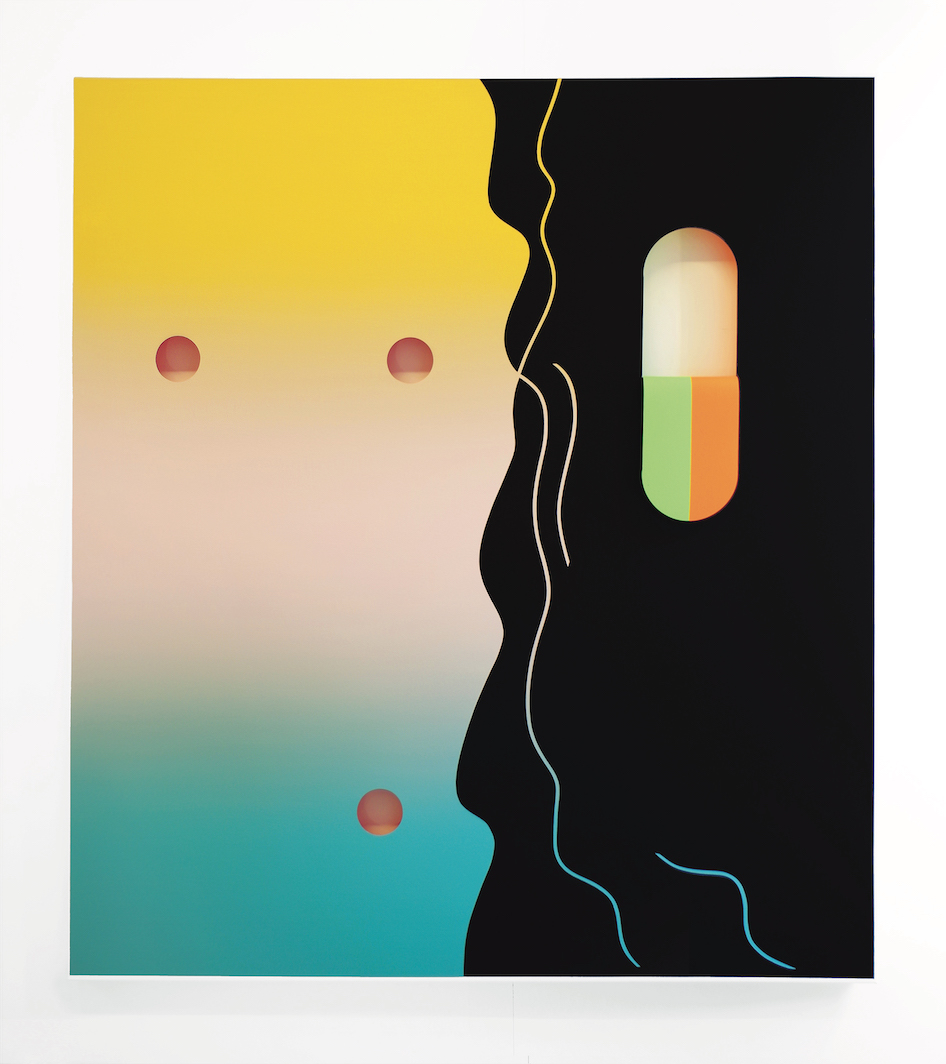

This perpetually interesting topic is also especially timely, since if one were to gauge by legal drug use alone, it looks like more people struggle with their mental health than ever before—or else prescribers are making diagnoses based on looser parameters, or both. In 2013, one out of six American adults were taking psychiatric drugs; as of this May, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates the number of Americans treating mental-health issues with prescription drugs is closer to one in four. A 2011 CDC report found that by the late 2000s, antidepressant use among all ages had risen by almost 400 percent since the early ’90s. From 2009 to 2018, the rise occurred among adult women, but not men. More than twice as many women as men take them.

Aviv is one of those women, a fact about which she is forthright and critical. “My first six months on Lexapro were probably the best half year of my life,” she writes, before saying she was “unnerved” by how many of her friends—“mostly white women—were taking the same drug.” Aviv’s friend Helen refers to the SSRI as “Make The Ambitious Ladies More Tolerable pills.” While Aviv fears she “will be on this drug for the rest of my life,” she’s already taken it for more than a decade, and thinks she requires it “to continue as the person [I’ve] become.” She believes she’s “endowed my pill of choice with mystical capacities—it contains the things I’m not but wish I was,” but also that the pill lets her live out her “baseline personality.”

Angst about overprescribing antidepressants has risen in concert with antidepressants’ increased prescription. But Strangers to Ourselves is about much more than that, even as Aviv retains her ambivalence about medication. Every story she tells is saturated with ambiguity, and there is no endorsement of any treatment, no confidence in any preventative or cure or even of any “problem,” at least not in the sense of an issue that arises from and remains within a single person, unique to their neurology. “Pathology emerges from within and is endured that way, too,” Aviv writes, “but [mental illnesses] are also made and sustained by our relationships and communities.” Aviv’s subjects—herself, four women, and one man, three living and three dead—were chosen because they “have come up against the limits of psychiatric ways of understanding themselves,” and so rerouted down different paths, ones that focus on the political, the familial, the chemical, the spiritual: any approach that might clarify the nature of “a self in the world.”

Aviv’s triumphs in relating these journeys are many: her unerring narrative instinct, the breadth of context brought to each story, her meticulous reporting. Chief among these is her empathy, which never gives way to pity or sentimentality. She respects her subjects, and so centers their dignity without indulging in the geeky, condescending tone of fascination that can characterize psychologists’ accounts of their patients’ troubles. Though deeply curious about each subject, Aviv doesn’t treat them as anomalous or strange. From the prologue, which recounts her childhood hospitalization in an anorexia unit, she situates herself among them. “The divide between the psychic hinterlands and a setting we might call normal is permeable,” she writes, when acknowledging “how easily” her own life “might have gone another way.” She is not an interpreter or a judge. She is an equal, and so readers become peers, too.

After Aviv’s girlhood, Strangers moves to Ray, a seemingly self-sabotaging DC-area doctor who sues a mental institution on the grounds that the staff neglected to give him antidepressants during his long stay. Then comes Bapu, an unhappily married South Indian woman who repeatedly runs away to pursue ascetic devotional practices. Next is Naomi, a Black single mother in the Midwest who spends fourteen years in prison for dropping her toddlers off a bridge. The story of Laura, a wealthy, white, overmedicated New Englander, follows, and the book closes with Hava, an anorexic Aviv knows from her time in treatment. I hesitate to be more specific in part because so much pleasure comes from encountering these stories through Aviv’s deliberate descriptions, but also because the details that would be lost in summary are crucial to Aviv’s thesis: an individual’s mind cannot be divorced from the circumstances within which it develops.

Each person here extensively documented their lives for years. Ray worked on a memoir and Naomi wrote a novel; Laura blogged, and Hava and Bapu kept journals. Aviv gravitates to these writings because the authors “tried to overcome a feeling of incommunicability,” and their words allow direct access to their points of view. What also helps, I think, is that so many of these people are women, and the majority of those women are mothers, including Aviv herself. Mothers are arguably the most maligned figures in the history of psychology, but in Strangers they are intensely sympathetic characters, acting under tremendous pressure with little or no help—victims, not villains. Bapu’s in-laws, living off her inheritance, mock and disrespect her; her husband uses her for sex and money, and she has almost no privacy or power in her own home. Naomi was twenty-four and overwhelmed by the grief of racial oppression when she took her twins to the bridge; she had another two children at home and was raising all of them alone in the wake of postpartum psychosis.

That women, especially those raising kids, may act “crazy” due to sustained abandonment, impoverishment, and/or abuse, and not because of biology or malice, is a radical hypothesis in medicine and in politics. When white supremacy is included among those oppressions, the proposition becomes even more revolutionary. Naomi initially rejects the diagnosis of mental illness in large part because white doctors label her awareness of racism as paranoid and “bizarre,” the symptom of a disorder. The book’s most unbearable reveal may be that while a psychiatrist cited Naomi’s fear of being gassed as “delusional,” she was in fact gassed by prison officials.

If the world is one element of what makes people crazy, it doesn’t distribute the effect evenly. Psychiatric convention too often ignores “where and how people live, and the ways their identity becomes a reflection of how others see them.” Place matters, race matters, gender matters, and class matters too profoundly and diffusely to be compartmentalized or downplayed. The high rates of antidepressant use among middle-age women, for instance, is often attributed to hormonal changes during menopause. But middle age often marks a time when women must assume care for their elders as well as their children, all while maintaining a job outside the home. Moreover, women have higher rates of depression than men for most stages of life. You can consult The Second Sex if you’re looking for some extrinsic reasons why, or perhaps the Supreme Court’s majority decision in Dobbs v. Jackson.

I explained this, the broad badness of reality, to the psychiatrist who prescribed me Wellbutrin last year while I half-heartedly pushed back on her diagnosis of depression. When I told her I believe the planet will become uninhabitable within my natural lifetime, which makes it difficult to act toward any idea of a future, she didn’t reply that I was wrong, or that I shouldn’t think that way. Nor did she imply, at any point, that I was chemically malfunctioning. She simply submitted that antidepressants might make me feel better. The drugs were, to a large extent, separated from the diagnosis, which gave me room to take them even as I rejected her assessment.

In the prologue of Strangers to Ourselves, Aviv touches upon the psychoanalytic conviction that coaxing a patient’s unconscious to the surface will provide them with the “insight” that frees them from their neuroses. Then, she gives an overview of the rise of the biomedical explanation of mental illness, which is (incorrectly, she explains) thought to reduce stigma. By the book’s end, it seems we’ve entered a new, more nebulous stage, a stage of less patient criticism or correction, and also of less interest in explanation of both cause and solution. It’s unclear why antidepressants or electroconvulsive therapy or transcranial magnetic stimulation work, but that has hardly made these therapies obsolete. And whether my depression arose due to biology or a rational assessment of the present moment had little bearing on my psychiatrist’s proposed solution. Similarly, Aviv’s doctor suggests she feels “isolated,” which could be either an unfounded feeling or an objective fact of her circumstance. He frames antidepressants almost as an instructional tool, something to help her be at peace; the source of her discomfort is moot.

The pragmatism of this approach suggests improvement inasmuch as someone who felt misunderstood or degraded by a label could theoretically reject it while embracing drugs regarded as the disease’s treatment. Still, there are unanswered questions that could preoccupy philosophers for entire lifetimes. Regardless of how warranted one’s melancholy and pessimism, is there a reason not to alleviate it? Who is served by a person’s hopelessness and enervation, and who is served by their six-week- or six-month-long trial run on a prescription? (It’s always presented as a harmless experiment, even if it’s likely to be long-term.) Do psychiatric drugs bring us closer to or farther from our “true” selves, if there is such a thing? And if a true self exists, is it necessarily desirable or good, a state of being to which we should aspire or be resigned? There’s something unsettling about antidepressants’ privileged position as the go-to treatment either way. “Even if I had never been clinically depressed,” Aviv recalls a friend telling her, “perhaps there was some misalignment between my mind and the rhythms of contemporary life.” Are we wrong, or is the wrongness outside of us?

Strangers suggests it may be both. The world, after all, has a way of seeping inside of us. Bapu suffers because of real injuries committed against her, and her diagnosis of schizophrenia seems totally legitimate. The real injuries don’t contradict the diagnosis—they are in fact mutually reinforcing. Bapu is “not treated as a credible witness to her own experiences” by hospital doctors, because of “colonial notions about the irrationality of Indian religions.” Naomi spirals in situations where her mental health is ostensibly being treated, because authority figures refuse to admit that white supremacy is real, compounding her paranoia and despair.

While contemporary psychiatrists’ “position of neutrality,” as Aviv puts it, “can feel violent,” the larger world is indisputably so. Aviv’s friend Helen ultimately finds pharmaceutical-induced cheerfulness “phony,” and, to her family’s disappointment, stops taking antidepressants. But Aviv stays on them because she feels like the interest and energy Lexapro generates, while “foreign,” is also “true.” On Wellbutrin I feel “like myself,” and the daily pill seems no more definitional of my personality or temperament (or, frankly, brain chemistry) than would taking hormonal birth control or an antibiotic, though I resist seeing it as a purely medical tool. My Wellbutrin is almost recreational, something of a treat, an alleviation of the psychic suffering visited upon any nominally attentive person. Aviv describes it best as a “motivational core.” It doesn’t change my conviction that in this world, in this moment, mental and emotional well-being are impossible. But it seems to help me experience the feeling of something mattering instead of only possessing abstract knowledge that it does, and the feeling is far more propulsive.

Aviv’s daunted respect for uncertainty is what makes Strangers to Ourselves distinctive. She is hyperaware of just how sensitive the scale of the self can be. Some people, when told they are anorexic or depressive, may embrace the diagnosis to the extent that it becomes integral to their identity and thus a self-fulfilling prophecy. Others may reject a diagnosis so emphatically that it endangers them, and those around them, and makes adequate intervention impossible. Most terrifying, the division between these two fates seems unpredictable, not charted along personality type or illness but subject to the varied influences of any given moment: one’s age, one’s mood, one’s familial situation. “It’s startling to realize how narrowly we avoid, or miss, living radically different lives,” Aviv writes. Vulnerability is endemic, and incurable.

Charlotte Shane is a cofounder of TigerBee Press and a frequent contributor to Bookforum.